We sat down with Fritz Hendrik IV to discuss his current exhibition at Harbinger Project Space, feelings of doom and optimism and the liminal space of color. In paintings, sculptures and 3D printed models, Hendrik cites a multitude of references in more depth of thought than he admits, asking large questions about the role of the artist and the role of art in our strange pandemic-stricken, climate-collapsing reality.

Can you introduce us to your exhibition ‘Core Temperature’ at Harbinger, and how it was initially conceived?

A lot of the process of building this show has been shaped by the circumstances. I wanted to make an interior for an abandoned house in the countryside. I applied for funding for that, which would have been a big project, but I got a smaller grant that didn’t cover that idea. So, the starting point of this exhibition was to shrink the empty house idea, and the exhibition evolved in the process. As time went on, and Covid-19 came, I wanted to involve that experience in an implicit way. Many of us were playing a lot of board games at home and that gave me inspiration for the exhibition.

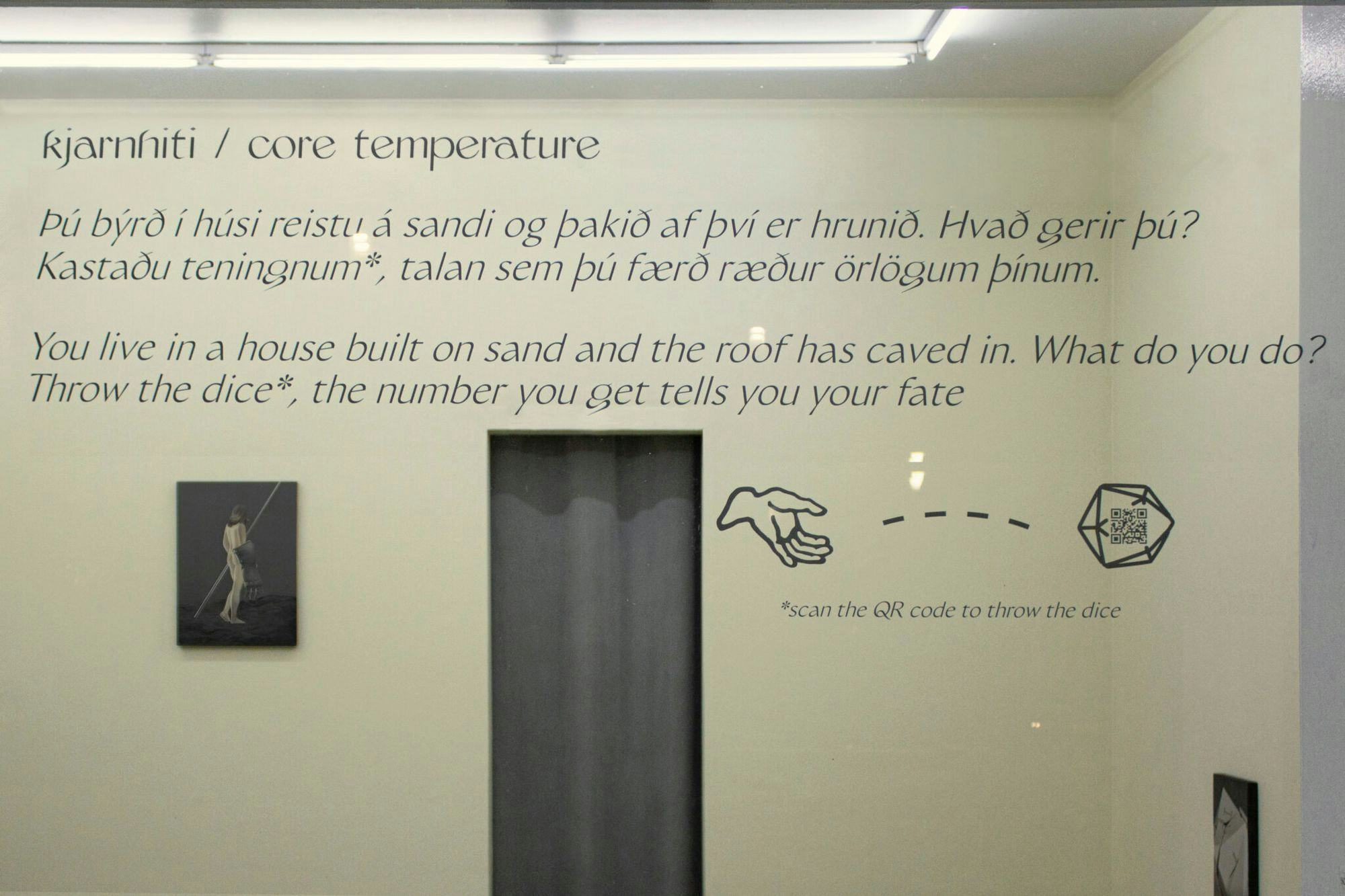

This year I tried the game Dungeons & Dragons for the first time, which was a really inspiring experience for me. I thought the premise of this board game was so interesting, because it’s basically improv. You have a narrator or storyteller, and he puts the players in circumstances. Then, the player has to react to a circumstance and throws a dice, and the dice tells him how successful he is in what he wants to do. That became the premise of the exhibition—to have this instruction on the window. There’s also a QR code that you scan, which brings up an animation of a dice being thrown, which always breaks.

I was inspired by thinking about this weird global situation, where you’re kind of always hoping for the best, and you have all these statistics telling you that you’re bound to fail—in terms of global warming and everything else. Yet, we always find ourselves thinking, ‘I’m going to do this, I’m going to recycle this, I’m doing something that is going to help.’ I have a persistent thought which is that, ‘this is not going to change anything’. There’s always a dice breaking, where you’re hoping for a result that never comes. I went into a doom mindset in the process of the exhibition, and I just let that run its course.

Can you tell us about the relationship between text and the visual works in your practice?

That relationship has always been something I struggle with. Text can act as a helpful invitation to start to think about the works. Also, I want to have it speak to people that are also not involved in visual arts normally, since text is a little bit more approachable. It can, however, also get to a point where text is feeding the viewer information and it becomes didactic. You know, like ‘this is how this works.’ I like text when it’s both inviting and informative, without telling you what to think.

We’re curious about the fictional character that often features in your work—Fræðimaðurinn (e. The Scholar)—is he present in your exhibition at Harbinger?

Actually, no. He’s absent in this exhibition. His existence in my previous work was practical. I wanted to poke fun a little bit at the theoretical aspect of contemporary art—the way that we always have to use theory as a crutch. I really liked the idea of making my own crutch, and of then externalising it in a character. Then, I have eliminated the need to have constant justification through theory, and am only justifying in a playful way. After that process, we could make him say all kinds of stuff.

Do you imagine the details of his character, how old he is and what he reads?

I imagine him like this 1960s existentialist philosopher, like Foucault or Sartre. He might even have the round spectacles as well. Philosophy isn’t something I’m an expert in, but when I have read these thinkers, they have really spoken to me and had a real effect. I’m really drawn to existentialists, even though I’m told they are very dated or problematic thinkers now.

Do you feel art should be allowed to tell a narrative?

That’s a question I ask myself all the time and I don’t really have an answer to it! I have the tendency to almost go the whole way of deciding everything in my work, with a set narrative and a set meaning but I always stop before I get to that end of the story, both for myself and for others to have some space and to determine an ending themselves.

There are traces of parafictioning, literature and philosophy, then, in your work. Where do you take inspiration from in other arenas of life?

I like to give myself the freedom to take inspiration from many different places—it’s never specific. In this exhibition, for example, there is the Dungeons & Dragons aspect, but there is also interior design, sports (in the lines on the floor). I’m not an expert in anything, and that’s the freedom you have as an artist.

Do you think about the role of the artist in a performative or formal sense?

Sure. I think about it in the same way as with most professions. How we act in certain ways to play out our roles in society. That is, actually, a big inspiration for all my work. For example, I take from Baudrillard this idea that everything is staged, in our society and in our culture. We can imbue things with meaning through a process of staging. For example, that’s how I approach painting. Painting is a really charged object. For me, it gives the idea that something is meaningful or important, merely by its form.

Do your paintings ever exist as their own entities outside of an exhibition?

I’m a little bit afraid to take the paintings outside of the installation, because I like them to have a sense of self and a consciousness. When paintings are in a setting like this show at Harbinger, I feel like they’re conscious of the premise, connected and self-referential, rather than existing as a stand alone object.

Core temperature, 2020. Installation view (detail). Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

It seems there is a partiality and peripheral quality to the figures in your paintings. We always see the back of a head, or the corner of a hand, for instance. Do you agree and is this sense of a close-up, reoriented gaze something you think about?

Yes, I think so. It’s similar to how I think about text—I want to invite somebody in, but I don’t want to tell the whole story, because I want to leave the picture to be finished in the head of the viewer. So, if an artist had to have the whole scene shown, you would have to have the whole idea from beginning to end visible. The cropped angle leaves more for the viewer to determine. Also, I like the idea of the archetype—the idea of the thing rather than an actual thing. For example, a hand is something you can really relate to, and it’s not a specific hand, it’s any hand.

How do you conceive of the viewer when you’re putting together an exhibition?

I like to think about the whole exhibition as a premise and an experience for the viewer. Because this exhibition is put up as an arena for a game, for example, I was uncertain about the role of the viewer. It looks like an invitation for participation. But when I thought about performances in the space or a physical interaction with the game, that was a complete turn off for me—I don’t want anyone to sit in the chair. So why would I make the chair? Maybe this is another aspect of creating scenes and staging—that they are somehow pristine and untouched.

What comes first, the making or the concept?

Definitely the making. Youtube has had a lot to do with the craft aspect to my work. The way you can teach yourself skills on Youtube has led me to most of the forms I create. For example, model making and 3D printing, which is something I’ve gotten into through the internet. I bought a 3D printer from China and there is a big community of model making online where you can engage in tutorials and discussions. I use that community in the making and the modelling process as a jumping off point. For example, the painting of the androgynous figure in this exhibition was a 3D image first. This is a method I’ve been using since I graduated. It gives off this unreal/real quality, yes, and a feeling of the too staged or clinical, which works in tandem with the formal quality of my work.

There is a very refined color palette that runs throughout your work. Does that come from an instinctual, formal place or somewhere else?

The color palette is both formal and conceptual. It has to do with the colors I gravitate towards on a strictly aesthetic level, but I also think the conceptual part of the color is usually thinking about the liminal or the in-between, where there are greyed out or muddied ideas. For example in this exhibition, the idea is quite nihilistic but playful at the same time. A kind of ‘positive nihilism’, which is an oxymoron, because it shouldn’t fit together. I really relate to the mindset of, ‘nothing matters, and that’s great!’ The colors are a reflection of that mentality and juxtaposition—they are both colorful and greyed out.

What are you working on at the moment?

Right now I’m thinking about electric outlets and batteries. Particularly, fictional electric outlets, which have a religious or spiritual, visual relation to icons.

Lastly, how do dreams function in your work and how do your real dreams influence your making?

I’m more of a mundane daydreamer than a night dreamer. I like to visualise and playfully think about things when I drift off, and I have good ideas just when I’m about to fall asleep. For me, dreams are useful for conceiving of things in an illogical or more free way than waking life allows, as a way of getting rid of the sense of the logical that we’re brought up with.

Yes, against sense making? Isn’t that why most of us are in the arts?

Yes—probably, definitely.

–

Fritz Hendrik IV has a secret exhibition about batteries that might be coming soon in Norway and may not be.

‘Core Temperature’ will be on view through the window at Harbinger Project Space until around Christmas time.