The International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia 2022 is titled The Milk of Dreams and is curated by Cecilia Alemani. The exhibition draws its title from a book by the surrealist writer and artist Leonora Carrington, in which various peculiar hybrid beings accompany grotesque poetic stories. Alemani uses Carrington’s creative vision to visually actualise a new way of approaching embodiment in today’s technological age whilst reflecting on the status of the human being in relation to other species and the earth.[1]

This theme is evident in one of the first spaces of the International Exhibition in Giardini. Half-formed bodies welcome the visitors: many-hued cyborgs, headless, with distorted limbs, made from lead crystal. The artworks are by the artist Andra Ursuţa, who creates the sculptures by mixing casts of her own body, everyday objects such as trash, and sci-fi imagery. As a result, these curious and eerie sculptures Bring to mind hybrid forms of futuristic horror films, such as Alien.[2]

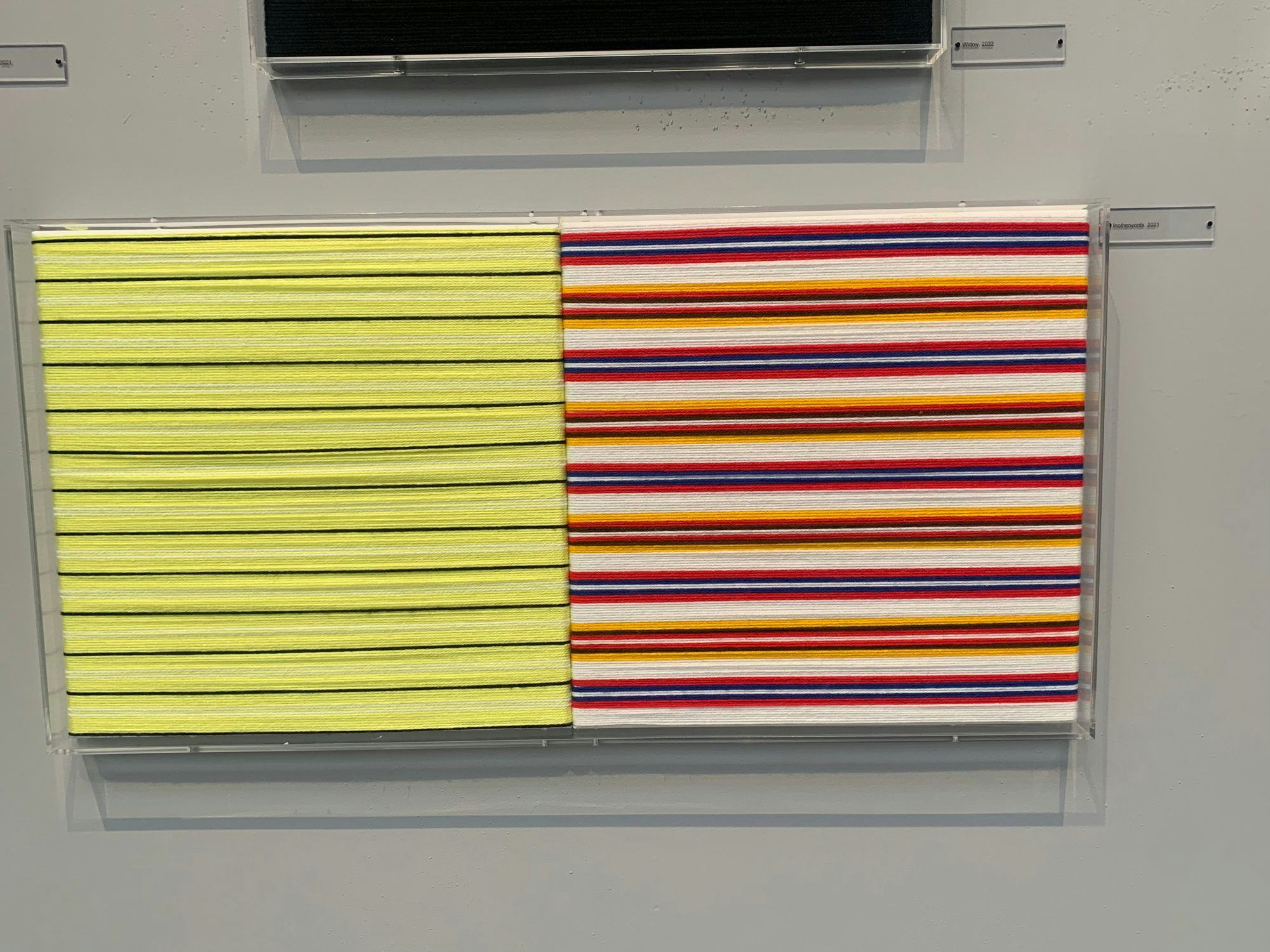

Andra Ursuța, Predators ‘R Us, 2020. Rosmarie Trockel, Textile Works.

On the walls of the same space, hang coarsely knitted textile works by the textile artist Rosemarie Trockel, surrounding Ursuţa’s works. They are minimalistic, massive, monochrome, brightly coloured, and evocative of modernist or abstract paintings. Trockel’s textile works date back to the 1980s, are highly political and provide a critique of the status of textile art within the art world whilst considering the role of women in a mechanised society. [3]

The pairing of these two artists sparked my interest. At first glance, Trockel and Ursuţa’s works have little in common, except that they can both be considered as feminists. The artists are from different generations; work with differing mediums; use separate materials; draw from unconnected inspirations, and have a dissimilar effects on audiences. Ursuţa’s works fit the Carrington theme of hybrid beings, but Trockel’s textile art speaks a different language: down-to-earth, everyday, and political. The space becomes a melting pot of the tensions between the different trends and ideas present in the exhibition as a whole. The artworks within The Milk of Dreams are multifaceted and range from Argentinian baking ovens by Gabriel Chaile to melted robot bodies by Tishan Hsu. My brain ached; I had the feeling that there was a thematic thread that I was missing.

So, I took a sip of the milk of dreams and decided to enjoy the ride. The first stop of my biennale journey was the biennale library, where I read the catalogue and took a look at the references in it. The library is located in Giardini, to the side of the international exhibition and is therefore slightly hidden. It contains a substantial collection of exhibition catalogues from previous biennales as well as other publications that have been used to inspire previous curators of the international exhibition.

I found out, while reading the catalogue, that Alemani uses Carrington’s story about The Milk of Dreams as visual and creative inspiration. She also uses the philosophy of Rosi Braidotti, a professor in contemporary continental philosophy and feminist studies at the University of Utrecht, whose work on posthumanism acts as a theoretical base for the exhibition.[4] I wasn’t sure what exactly posthumanism entailed, and so it soon became clear to me that in order to answer my earlier questions about how the exhibition fits together, I first needed to answer the questions: What is posthumanism? How is it used within The Milk of Dreams?

From my initial reading about posthumanism, I gathered that it was a departure from the humanism that became prevalent after the turn of the 20th century. After Nietzsche killed God, humans and their rationality became the agency of change in the world. [5] Humanism isn’t an all-bad ethical stance; it has shaped many contemporary ideas, such as human rights.

However, times have changed, and according to posthumanism, the humanist mode of thinking is inadequate in explaining or assessing contemporary problems. Natural disasters take place frequently, global warming has reached a point of no return, and many of us doubt the ability of human beings to tackle these conditions we have created. In turn, many doubt the centrality of ‘man’ in the natural world and his status in relation to other forms of life. Parallel to this change in attitude, there has also been an awakening about the knowledges of groups that live more in tune with nature. The rational, homogenous, and white ‘man’ of humanism that should have been so free and powerful is therefore obsolete. Despite the good that humanistic thinking has brought, not all groups have, historically or presently, had equal access to be classified as a ‘man’ and, accordingly, their lives are accordingly not valued on the same footing as his.[6] This reversal in ways of thinking or attitude, as well as the change in external circumstances of the current moment, is what Braidotti calls “a historical posthuman condition.”[7] Thus, posthumanism is a philosophical inquiry that cartographises this condition in order to understand it better. [8]

After this initial reading, I realised the importance of, when attempting to visually present the posthuman condition, having feminist textile art in one of the first spaces in Giardini. The artistic qualities are obvious, yet the artworks wouldn’t have been considered visual art until recently. It is, therefore, political in its nature, by de-centring the ‘male’ in art and the artist. Other examples of textile art that would have been considered ‘craft’ in the past can be found throughout the exhibition: embroidery, tapestries, patchworks and textile sculptures.

Inotherwords, Rosemarie Trockel, Inotherwords, 2021

The posthumanist thread was clear for me in textile art. However, I still had some difficulty wrapping my head around the position the exhibition took towards the ‘posthuman condition’ and technology – it seemed too passive and positive. The next stop of my journey was, therefore, a space in Arsenale titled Seduction of the Cyborg, which is dedicated to Donna Haraway’s philosophical reflections about the cyborg. According to her, we are already cyborgs. We don’t need prosthetic limbs or artificial brains since everything we do to our bodies to enhance them to prolong our lives is part of the cyborg.[9] For example, our lives have become longer due to medical science, and the internet and smartphones have mutated the way we communicate and behave in our everyday. We can connect to anyone anywhere at any given time, and we have all information at our fingertips always. Technology has changed our identities as humans, and we influence technology. Haraway sees the cyborg in a positive light and imagines the cyborg to be a collection of many parts rather than a whole, which could change our future ways of thinking about the world and ourselves from the narrow ideologies of universal holistic theories into seeing the world as a collection of related things coming together.[10] Technology and nature are not two distinct entities, but collide in the cyborg and become a continuum. The technological part of the cyborg is dependent on its ‘earthly’ part, and vice versa, which has the effect that in the world of the cyborg, the dualism of nature/culture is challenged – the cyborg is both at once. [11] We should not fear the cyborg because we can be responsible for the social connection between science and technology.[12] We, the cyborgs, can use this new condition as a spark for feminist creativity, and in the exhibition, The Milk of Dreams, a visual demonstration appears, which is hopeful: posthuman and postgendered.[13]

Rebecca Horn, Kiss of the Rhinoceros, 1989

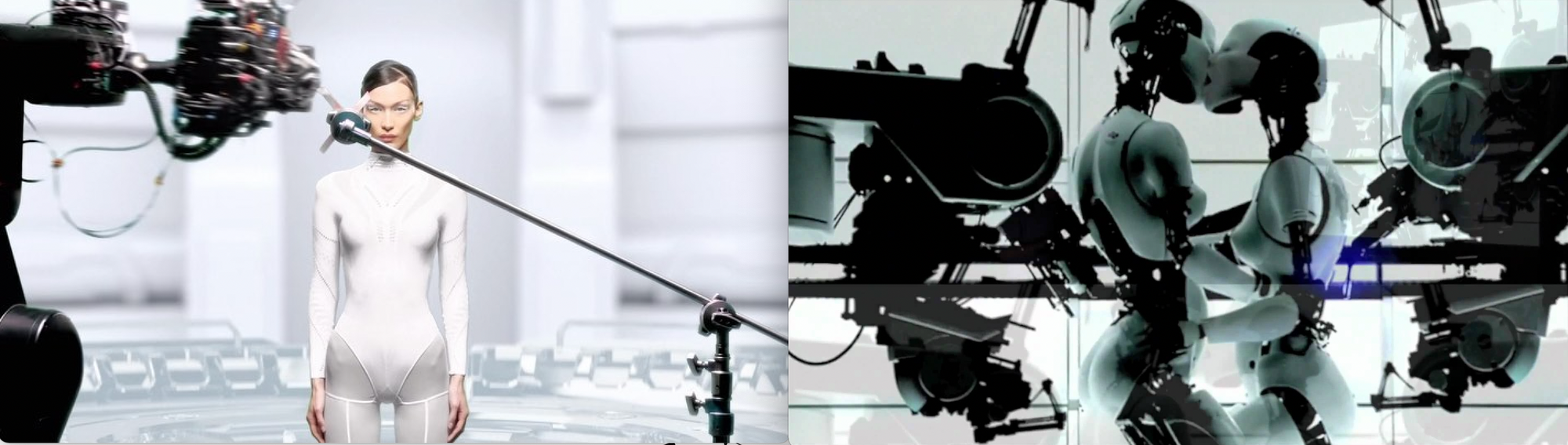

I understood the idea, but it didn’t quite match my experience. The transformation of humans into cyborgs or future beings permeates the present in a somewhat negative way. I sometimes feel as if the desire to gain full control of one’s body so as to make it almost supernatural is evident everywhere at the moment; people want to live longer, work more, sleep less, be more beautiful, and maximise themselves. This longing is prevalent in pop culture with figures like Bella Hadid, or CY-B3LLA,[14] as well as Kim Kardashian and the fashion house Balenciaga at the forefront. [15] In my mind, the longing is capitalised by a hyper-humanist agenda that sells, with a certain aesthetic, the idea that it is possible to fix anything that we might consider shortcomings through technology. However, this is only the capitalist ideology of the rich. Those who are wealthy will become cyborgs, and it is unlikely that the people who didn’t have access to Covid vaccinations will ever come close to the cyborg.

Hannah Levy, Untitled, 2022

The longing to become a half-human, or future-being, has another, related wing within feminist fringe pop culture, one that embraces Donna Haraway’s hopes. It appears in the aesthetic of fringe pop musicians such as Grimes, FKA Twigs, Björk and her collaborator Arca, but they all assume an almost half-human and sometimes unearthly appearance. [16] The exhibition has much in common with the fringe pop and exalts techno-future imagery and the cyborg. For example, in Giardini, there are on display ultrahigh metal high heels by the artist Hannah Levy that I could easily see Grimes or Arca wearing in a music video or at a fashion event.

Visually, there is minimal difference between the longing to perfect ourselves, so to speak, into an quasi-robotic state, which, to my mind, represents a kind of capitalist hyper-humanism (or trans-humanism), and the positive posthumanist visual manifestation of the cyborgs in The Milk of Dreams. There seems to be too short a distance between the visual representations of the uneasy desire of everyday life and the fringe pop aesthetic, which I actually admire. To some extent, both are connected to the same capitalist culture industry. For example, fringe pop icon Grimes recently had her second child with the tech-savvy millionaire Elon Musk. So there must have been some kind of nuance or approach that I was missing.

To the right a still from Bella Hadid’s instagram post, 2022. To the left a still from Björk’s video to the song All is Full of Love, 2009.

After having felt this tension in my stomach for a few weeks and letting it digest a little, I made the last stop on my journey. The stop was a talk held by the Biennale with Rosi Braidotti about posthumanist feminism. The event can be found on the YouTube site of the Biennale, and in it, Braidotti speaks with such enthusiasm that it was difficult not to get infected by it. She started by emphasising the importance of a critical attitude towards the ‘posthuman condition.’ Technology and nature are not opposites, yet we can think twice about what kinds of cyborgs we are (since we are all already cyborgs). She takes a stance against the goal of refining the human endlessly, as it involves a fundamental misunderstanding of what it is to be a human being. “The brain is not a black box that you can abstract from the rest of embodiment, it is embodied and embedded, we think with our entire bodies.” [17] The posthumanist feminist stance towards technology is, therefore, a “yes, but” attitude, according to Braidotti. She participates in the excitement of the technological advances while not sharing the euphoria and inhumanism in wanting to become a super-human. She then added that she hoped that Elon Musk would go quickly to Mars and that he would stay there.

Andra Ursuța, Impersonal Growth, 2020 & Canopic Demijohn, 2021

To me, the prosthetic limbs and space-grafted bodies of Andra Ursuţa, became dystopian. The artworks became a type of critique of the ‘posthuman condition.’ Perhaps it was always supposed to be a critique or a dystopian visual representation of what could happen if technology takes the wheel. Paired with the textile works, both artworks had a clear voice: It matters how the future of the cyborg is approached in visual art and pop culture and in what context they are examined. For instance, Grimes’s feminist cyborg statements seem to be hollow words considering her position within pop culture: while a similar aesthetic theme thrives in another context, such as with Björk, who has devoted her artistic pursuits to feminist revision of the human being and its status within nature.

I think that the context really might be the only difference between the aesthetic of the feminist cyborg and the capitalist one, but the barrier is thin. The context of The Milk of Dreams elevates the cyborg whilst warning against it simultaneously. The exhibition seemed to me, after my journey, a carefully thought-out ideological patchwork that, at first glance, seems to be randomly asserted. When given a closer look, the sewing and choice of fabric were elegant and precise. However, I still question the status of the cyborg: Is there a difference between the capitalist and the feminist cyborg when they look almost identical? Is context we’re given sufficient? Is the time of Haraway’s hopefulness over? Can we really take responsibility for the social relations with technology? Or are we already in Ursuţa’s dystopia?

[1] Cecilia

Alemani, “Statement by Cecilia Alemani,”

https://biennialfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2.-Statement-by-Cecilia-Alemani.pdf

[2] Madeline

Weisburg, “Andra Ursuţa,” https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/milk-dreams/andra-ursuţa

[3] Madeline

Weisburg, “Rosemarie Trockel,” https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/milk-dreams/rosemarie-trockel

[4] Cecilia

Alemani, “The Milk of Dreams,” The Milk of Dreams Exhibition, interviewed

by Marta Papini, 2022, 26-27.

[5]Diane Marie

Keeling og Marguerite Nguyen Lehman, “Posthumanism,” April 26, 2018, https://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-627

[6] Rosi Braidotti,

“Posthuman Critical Theory,” The Milk of Dreams Exhibition, 2022,215.

[7] Rosi Braidotti,

The Posthuman, 6.

[8] Rosi Braidotti,

The Posthuman, 4.

[9] Donna Haraway,

“You Are Cyborg,” Wired, interviewed by

Hari Kunzru, February 1, 1997, https://www.wired.com/1997/02/ffharaway/

[10] Donna

Haraway, ACyborg

Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,

(University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 67.

[11] Haraway,

ACyborg Manifesto, 9.

[12] Haraway,

ACyborg Manifesto, 67.

[13] “Seduction

of the Cyborg,” The Milk of Dreams Exhibition, 2022,

499.

[14] Alex Frank,

“Bella Hadid Arrives in the Metaverse With a New Line of NFTs,” Vogue, June 21, 2022, https://www.vogue.com/article/bella-hadid-nft-metaverse-interview See also https://cybella.xyz

& Daniel Rodgers, “The model is releasing 1,111 NFTs under the pseudonym CY-B3LLA,

including a cybernetic warrior woman and a BDSM-inspired robot,” Dazed, June 22, 2022, https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/56381/1/cy-b3lla-bella-hadid-nfts-discord-cyborg-rebase-metaverse-sex-bot-web3

[15] Angel,

“Robotic suits and cybernetic faces a debut for Balenciaga’s Spring 22 Campaign,”

RUSSH, November 5, 2021, https://www.russh.com/balenciaga-spring-22-campaign/

[16] Björk,

All Is Full of Love, music video directed by Chris Cunningham,

May 24, 1999, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EjAoBKagWQA

[17] Rosi Braidotti,

seminar on Posthuman Feminism hosted by the Venice Biennale, Meetings on Art: Posthumanist Feminism, June 11, 2022,

https://youtu.be/JpwuycDAEbc?t=2295 “We all know what Elon Musk is up to

by giving barcodes instead of names to his children and putting his billions in

the service of creating life on Mars; well I hope he goes quickly and stays there”-

37:20

-icelandic-pavilion-2000x2667.jpg&w=2048&q=80)